Language labs: an overview of the trends

Abstract

Modern language labs offer a wide range of

language-learning services and facilities; they therefore require developed

administration and state-of-the-art technical infrastructure. Some modern

language labs are also involved in innovative research, training services and

informational services. This article will present key trends in language-lab

development from approximately the 1950’s

to the present day. It will therefore describe the history of language-lab

advancement, some implications of behaviourism and constructivism, autonomy as

a construct, the digital revolution, and modern language-lab services.

1. Introduction: establishing the language lab

Language labs

are chiefly used in schools, colleges and universities. They are sometimes also

referred to as language resource centres, multimedia labs, centres for language

study, language learning centres, interactive media centres, language and

technology centres, media centres, open access centres, foreign language

centres, open learning centres, open access multimedia centres, self-access

centres, individualised language learning centres, independent learning

centres, CALL centres/labs, world media and cultural centres, language

acquisition centres, and language and computer laboratories.

The perceived need to teach war-zone

languages in the Second World War and the subsequent onset of the Cold War

brought about, under the aegis of the US Armed Forces Institute and the

American Council of Learned Societies, development in methods for teaching

foreign languages (Toth

2003). The US

Army used the audio-lingual method as early as 1942. By the 1950s language labs began to emerge from

the chrysalis of this war-driven language-learning development momentum.

Progressive universities spearheaded this metamorphosis by developing

impressive inventories of mostly tape-recorded language-learning materials and

increasingly inviting infrastructures in which to utilize these materials.

However, in retrospect, one might question why language labs had not become

widespread earlier. In the US for instance, in 1913 Diamond-Disc players

were beginning to be sold, commercial radio came into operation in 1920, the first commercial sound

film with spoken dialogue was achieved in 1927, the first magnetic tape recorder

was demonstrated in Berlin in 1935

and in 1949, 7-inch 45rcm micro-groove vinylite records were

introduced (Schoenherr

2005).

Language labs established

themselves as centres of language learning contemporaneously during the rock

and roll years of the 1950s

and 1960s;

technological breakthroughs during this period were catalysed by the enticing

rewards of musical entertainment and language labs were on the whole fortuitous

beneficiaries of these market-orientated advancements. Key achievements during

this period seem analogous in merit with recent 2001-2007 developments in portable music players. They

included the transistor

portable radio (1954),

the stereo LP (1958), the compact audiocassette,

the first home Sony

video tape recorder (1963),

and Dolby Noise

Reduction (1968).

The International Association for Language Learning

Technology (IALLT)

was established in 1965;

it is a professional organisation that attempts to provide leadership in the

development, integration, evaluation and management of instructional technology

for the teaching and learning of language, literature and culture.

2. Behaviourism and

constructivism

Although recording technology during the 1970s and 1980s continued to progress, language-lab

approaches apparently began to fall out of favour (Garcia

and Wolff 2001,

Davies

et al. 2005). Significant 1970’s technology comprised the 4-hour VHS tapes (1977), the Sony Walkman audiocassette player

(1979) and the video camcorder (1980). The reason for this perceptible loss of

self-efficacy for language labs most likely had its roots partly in the

methodological move away from structural approaches to language learning, to a

flurry of novel, outwardly sturdy but often transient techniques for

second learning acquisition. Well-known such approaches include: The Silent Way

(Gattegno 1972);

Total Physical Response (Asher 1969);

Community Language Teaching (Curran 1976);

Suggestopedia (Lozanov 1978);

Communicative Approaches (Brumfit and Johnson 1979, Widdowson 1978, Yalden 1983); The Natural Way (Krashen and Terrell 1983).

Even though

behaviourist theory with its asserted filling-the-blank-slate

(Beatty 2003, 94), rote-learning and repetitive

drilling (pejoratively known as ‘drill and kill’ Warschauer and Healey

1998) came under a ‘cognitive’ attack from Chomsky in 1964, strangely it is

still discussed and compared to the now trendy and dominant constructivist

model in modern CALL literature. Beatty (2003, 91) for instance attempts to

elucidate how constructivism differs radically from behaviourism suggesting

that learning is a process by which learners construct new ideas or

concepts by making use of their knowledge and experience; the learner ‘has

greater control and responsibility over what he or she learns’ (Beatty 2003,

91). Beatty (2003, 99-100) also asserts that collaboration

is an important activity in CALL as it encourages

social skills and thinking skills and it mirrors the way in which learners

often need to work once they leave the academic setting. There is also an

imposing and compelling literature base that discusses the benefits of

collaboration (e.g. Candlin 1981; Chaudron 1988; Ellis 1998; Nunan 1992). Modern language-lab Web pages also often

refer to the concept of taking control and responsibility over learning; for

instance in the Directed

Independent Language Study programme on the Yale University’s Center for Language Study

Web page, it is stated that students ‘must be

self-directed and self-disciplined, and they must be willing and able to assume

full responsibility for their learning’.

3. Autonomous learning as a construct

Autonomous learning is now a language-lab buzzword; it has therefore become a feature of self-access centres

(or language labs) (Benson 2001,

114). For

instance, the University of Hull’s Open Learning Centre

states that students can work independently on language learning in a

comfortable and well-resourced environment or the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s

Modern Languages Lab

maintains that lab work is of an individual, independent nature and that

instructors ‘may check’ lab work. Moreover, Davies

et al. (2005,

10) state that with

regard to complete commercial language courses (courseware) to be used online,

facilitated through a language lab, the general consensus of opinion is that

one principle of usage should reflect the need to allow the learner to proceed

from dependence to autonomy in any learning activity. Benson (2001, 35)

states that recent research in the field of autonomy has drawn freely on

research in the constructivist tradition within which works of Kelly (1963); Barnes (1976), Kolb (1984), Vygotsky (1978) have been especially

influential. Benson (2001,

8) maintains that

autonomous learning is learning in which the learners themselves determine the

objectives, progress and evaluation of learning. It also has a robust

literature base (e.g. Breen and Candlin 1980; Little 1997; Riley 1988). Benson (2001, 22-46)

holds that the concept of autonomy in language learning has influenced and has

been influenced by a variety of approaches within the field (e.g. Kilpatrick 1921; Freire 1974; Rogers 1969). Yet, Benson (2001), who maintains a

comprehensive online bibliography on

autonomy, in his book on autonomy in language learning is somewhat tentative

when he summaries that:

We still know relatively little about the ways in

which practices associated with autonomy work to foster autonomy, alone or in

combination, or about the contextual factors that influence their

effectiveness. We are also unable to argue based on empirical data, that

autonomous language learners learn languages more effectively than others, nor

do we know exactly how the development of autonomy and language acquisition

interact. (Benson 2001, 224)

Personalised

learning is about tailoring education to the individual need, interest and

aptitude so as to ensure that every pupil achieves and reaches the highest

possible standards (Becta

2006a, 4); it is therefore closely associated with autonomous learning in

which the learners themselves determine the objectives, progress and evaluation

of learning (also held by Condie

and Munro 2007, 6-7). The Oxford

University Language Centre Lambda Project for instance is in effect developing

personalised learning when it investigates

how learners can best maintain and develop their language skills independently.

Moreover, the British Educational Communications and Technology Agency (Becta) in a plethora of recent publications

(e.g. Becta

2006b; Becta

2007a; Becta

2007b), seems to be propagating the construct of personalised

learning; yet personalised learning might also be mutating the learner-teacher

bond. The Condie

and Munro (2007, 6-7) report, for instance, a major study on the impact of ICT

in schools, commissioned by the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) and Becta in the UK, is hesitant

with regard to the impact of personalised learning on classroom

relationships:

A persistent

theme in the literature is the extent to which ICT can make the learning

experience more personalised, more targeted at the needs of the individual

learner. Combinations of technology and applications give greater choice in

relation to what, when and where to study, selecting according to interests,

learning styles and preferences and need. Such systems can give the pupil more

autonomy and independence with regard to learning and a range of sources to

draw on. This can be unsettling for some teachers and may well change the

dynamics of the pupil-teacher relationship. There is little in the literature

on the potential impact on relationships in the classroom as schools develop

e-capability and use ICT to support the learning process more widely. Condie and Munro (2007,

6-7)

Appertaining to the impact of ICT on attainment, Condie and Munro (2007, 4) also appear tentative when stating

that ‘at present the evidence on attainment is somewhat inconsistent, although

it does appear that, in some contexts, with some pupils, in some disciplines,

attainment has been enhanced’.

Nonetheless;

Becta

(2006b, 16) states with regard to personalised learning spaces that ‘the

potential to enhance the learning experience is immense’; Becta

(2007a, 1) maintains that ‘personalised learning is a major goal in both

the proposed 14-19 reforms’ and ‘the embedded use of ICT supports and delivers

personalised learning’; DfES

(2006, 5) holds that it is an educational priority to ‘establish a clear

vision of what personalised teaching and learning might look like in our

schools in 2020; Condie and Munro (2007, 6-7) state that the UK Government’s

e-strategy sets the expectation that by 2008 every pupil should have access to

a personalised online learning space; Becta

(2007b, 5), with regard to ICT and e-learning in further education,

however, emphasises that the use of ICT to personalise learning is ‘at an early

stage and still has a long way to go’.

In light of the above discussion regarding

autonomy/personalised learning, modern language labs may be faced with a

possible contentious issue: is learner autonomy (or personalization of

learning) in practice a sufficiently workable construct for

justifying the pursuit of the ‘bleeding edge’ (Beatty 2003, 71) new tools in ICT or are the new ICT tools an

appropriate cost-effective apparatus for developing the possibly

terminologically and conceptually confusing (Benson 2001, 1) construct of learner autonomy?

4. The digital revolution and self-access

The onset of the

digital revolution in the early 1980s

with its CD-ROMs (1985), DVD players (1996), MP3 players (1998),

Apple Computer iPods (2001) and the comprehensive advancement in computer hardware/software,

reliable Internet services and wireless technology

devices provided new tools for language labs.

Benson (2001, 114) argues that historically self-access centres

(or language labs) have occupied a central position in the practice of autonomy

and many teachers have come to the idea of autonomy through their work in them.

A self-access centre is essentially a language lab in which learning resources

such as audio, video and computer stations, audio/videotapes, computer software

and printed materials are made directly available to learners. Examples of some

self-access centres can be found at the University of Cambridge, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the City University of Hong

Kong, the University of

Hull Language Institute, Middlesex University, University of Colorado-Boulder,

Yale University, Oregon State University,

Indiana University,

University of Albany, University of Nebraska Lincoln,

University of Houston, Oxford University, Michigan State University, Sussex University, Princeton University, Purdue University,

Ohio State University, Ohio ESL, Carnegie Mellon University, John Hopkins University, Rice University, University of Oregon, Washington

University, Hawthorne-Melbourne

University.

However, whether or how the users of such self-access centres use

centre materials in a way that enables them to construct new ideas and so take

control over their own learning (autonomy/constructivism) or drill and repeat

(behaviourism/audio-lingual) seems less relevant than whether there is any

measurable outcome for the learner or tutor. Moreover, it could be argued that

structuralism is on the rise as a result of the numerous ESOL

interactive Internet exercises that have become available on well-known CALL sites; many

such exercises, at least at the moment, seem to be narrowing foreign language

teaching to mainly structural grammar and vocabulary (Alexander 2006, 2007).

5. Language-lab facilities

Modern language labs offer an extensive and growing range of

services to users. Most of the services relate to offering a variety of modes

of learning foreign languages and developing a corresponding assortment of

materials for such languages. As a

result, such language labs often have a developed administrative and

state-of-the-art technical infrastructure. Another area that modern language

labs are widening pertains to innovation and development. The Center for Language Study at Yale University

for instance engages in professional development,

provides funding for

research or attempts to strengthen

language programmes taught at the University. The Cambridge University

Language Centre on their research and

development e-link maintains that the ‘language

learning and teaching activities of the Language Centre are underpinned and

informed by relevant research in second language acquisition and educational

technology’. Princeton University Language Resource Center receive support from

the Educational

Technologies Center and so build

and maintain tools for teaching and research.

Screenshot 1

Princeton University

Language Resource

Center

Screenshot 1 presents an example of a language-lab homepage

offering extensive services. The Language Resource Center at Princeton

University states that it provides ‘resources and facilities to support the

study of foreign languages, literatures, and cultures’; moreover it also states

that it supports independent language study and assists Princeton University

faculty in incorporating video into instruction.

5.1

Language-learning materials’ related

Language labs offer a broad range of learning

materials and modes of language learning. This range includes the use of: CDROMS (Chinese University of Hong Kong), English

newspapers (Sussex), general

language links for students (used at Sussex), video conferencing (Michigan State), MP3s (Colorado-Boulder), language

learning centre blog (current awareness for

students, used at Sussex), multimedia library (Colorado-Boulder), materials

catalogue (Colorado-Boulder),

self-access

and independent learning

(City University of Hong Kong), language

Podcasts (Washington), self access services (Middlesex), film,

video and digital media (Princeton), language

buddies (Victoria

University of Wellington, ‘Language Buddies’ are

native speakers of different languages who help each other improve language

skills), audio

materials listing (Indiana), international television broadcasts

(Indiana). Language labs also usually offer a variety of online language links;

the following labs offer a wide range of Internet language links: University

of Colorado-Boulder, Indiana

University, Languages On-Line

(Indiana University), University

of Nebraska-Lincoln, University

of Houston, Washington University, John Hopkins University, Cambridge University, Oxford University, Michigan

State University, Princeton

University, Ohio ESL, Rice

University, Yamada Centre, Washington

University.

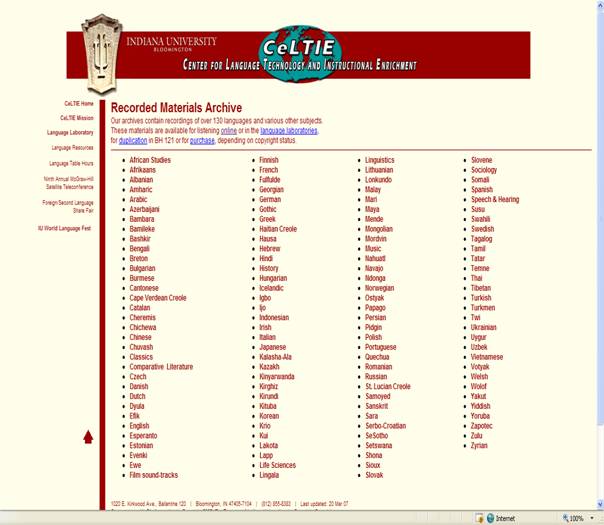

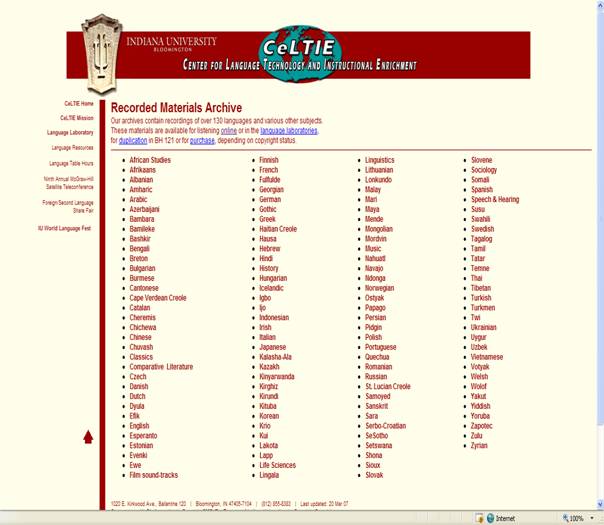

Screenshot 2

Online language materials at Indiana

University

Indiana University, in screenshot 2, provides archives of over 130 languages available for

listening online

or for use in language laboratories.

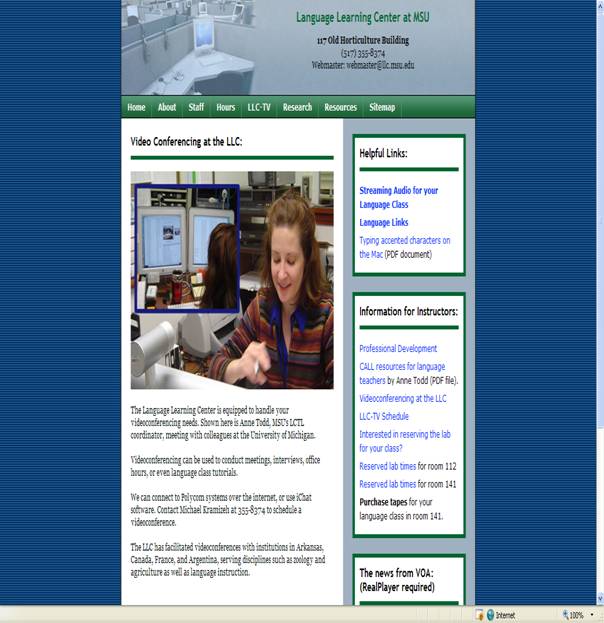

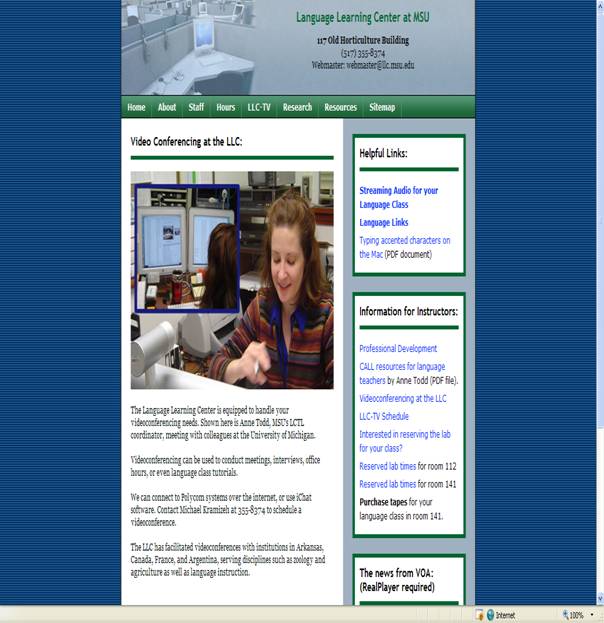

Screenshot 3 Videoconferencing

Screenshot 3

provides an example of the videoconferencing facility at the University of Michigan’s

Language Learning Center.

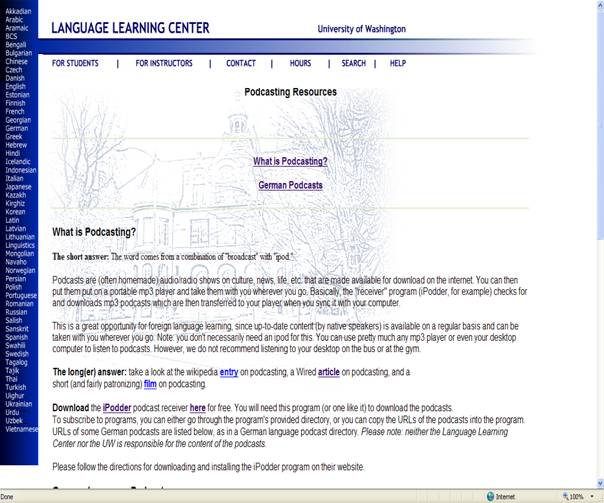

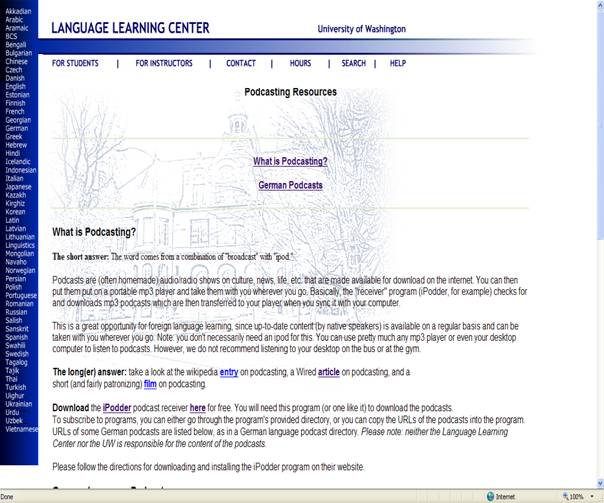

Screenshot 4 below explains how the University of Washington’s

Language Learning Center uses

Podcasts with up-to-date content for language learning.

Screenshot 4 Language

Podcasts

5.2 Developmental-related

Some language labs provide a gamut of innovative testing and

training services for students and staff. Some of these services include: professional development (Yale), e-testing

services for students (Oxford), directed independent language study for

students (Yale), technology training for staff

and students (Albany), foreign language technology certificate

for staff and students (Colorado-Boulder), language classes for staff and students

(Colorado-Boulder), consulting,

design and training (Princeton).

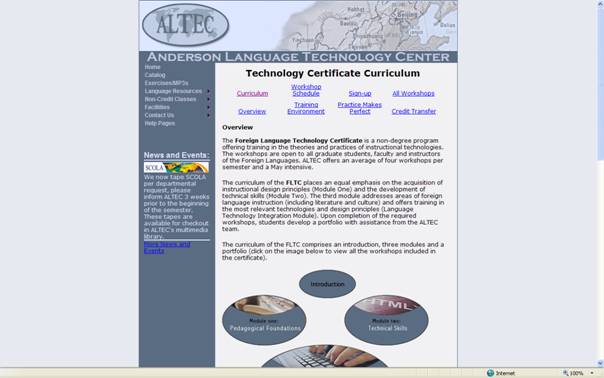

Screenshot 5

The Technology Certificate Anderson Language

Technology Center

The Foreign Language Technology

Certificate presented in screenshot 5

at the University of Colorado-Boulder offers training in the theories and

practices of instructional technologies. The workshops are open to all graduate

students, faculty and instructors of the Foreign Languages.

5.3

Administrative related

Modern language labs require developed administration; some typical

administrative tasks comprise responding to a faculty/staff

helpdesk (Albany), a student

helpdesk (Albany), a Web helpdesk (Middlesex) or a technology help link (Colorado-Boulder). Other duties involve

presenting lab staff (Yale), providing materials

purchase information (Indiana), submitting recorded

materials (Indiana), giving information about contact

and location (Yale) and adhering to lab opening hours (Colorado-Boulder). Another important

administrative undertaking pertains to audio-tape

check-out (Indiana),

tape drop-off and

pickup (Nebraska-Lincoln), lab check-in and

checkout (Nebraska-Lincoln) and general lab scheduling.

5.4

Technology-related

Modern language labs also need to

have a developed and functional technology infrastructure; some of the

technology considerations include: WebCT (Houston),

lab services (Houston),

lab equipment and

services (Houston), PC classrooms

(Colorado-Boulder), video

viewings in class (Yale), Mac classrooms

(Colorado-Boulder), studio

recordings (Yale), technology services

(Yale), media conversion

and duplication (Yale), software and hardware (Albany), technical related links (John

Hopkins), equipment available for short-term use

(Michigan State).

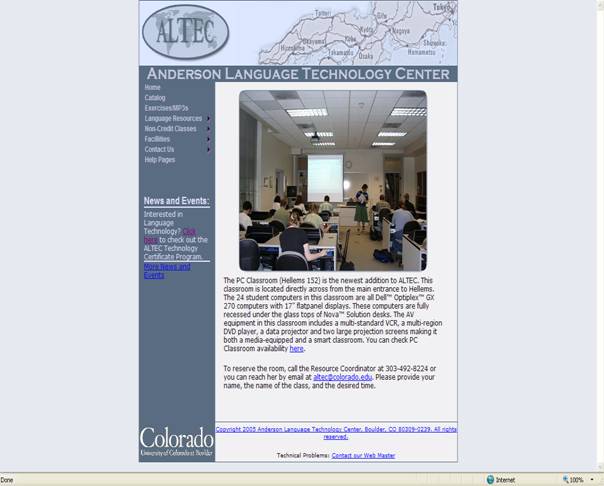

Screenshot

6 The Anderson Language Technology

Center PC smart classroom

5.5 General lab related

Moreover, language labs offer

additional related informational services such as: intellectual property and copyright (Yale), funding opportunities (Yale), seminars and presentations (Yale), news and announcements (Yale), mission statement (Houston), frequently asked questions

(Yale), lab

tour (Nebraska-Lincoln),

innovation and development (Yale), research and development

(Cambridge), regulations and policies

(Middlesex), provision for disabled

students (Middlesex), services for

distance learners (Middlesex), dyslexia support

(Middlesex), audio homework, audio

portfolios, digital worksheets (Michigan State), computational

science and engineering support (Princeton), database application

services (Princeton), educational technologies center (Princeton), education and outreach services (Princeton), scholarships (Ohio State), individualised instruction

(Ohio State).

Screenshot 7 Individualized

Language Learning Center

6. Conclusions

The development

of recording technology since Edison’s then

ground-breaking recording of a human voice on the first tinfoil cylinder

phonograph in 1877

has therefore been unremitting despite the technical and financial difficulties

faced by the industry’s pioneers. The relatively recent emergence of numerous wireless devices

that transfer and receive information and the appearance of progressively more

sophisticated e-learning platforms and authoring tools is pushing the evolution

of ICT up a gear making it increasingly challenging for language labs to

keep up or increasingly risky for them not to. The escalation of

technological innovations however may be redounding to the benefit of those

that create the technologies and is opening a Pandora’s e-box of wonders and

wizardries (or possibly ‘gimmicks’ Coughlan 2007) that are now portending

relatively impulsive change in language education. Some of the latest

buzzwords include: moodles, virtual

learning environment (VLE), course management system (CMS), learning

management systems (LMS), podcatching and

podcasting, video technology and

applications, authoring,

chatting online,

chatting

in 2007, Internet radio,

education-oriented

MOOing (e.g. SchMOOze), audio

technology and applications, learning and using

HTML, information on

technical issues, finding where to

download software, skypecasting, WebCT,

blogging

(vlogging), webcasting, moblogging,

iPod,

virtual

reality (VR) environments, LAMS: learning activity management

system, learning platforms,

video conferencing,

personal broadcasting

with third generation mobile phones, augmented reality and

enhanced visualisation, context-aware

environments and devices, educational gaming,

e-safety,

blended

learning (hybrid/mixed), m-learning,

distributed learning,

e-mentoring or e-tutoring.

Autonomous language learning is now

the vogue and the construct as stated previously has a strong and persuasive

theoretical underpinning; it seems the ‘autonomous learner’ and the felicitous

advancements in ICT have become seemingly

ideal partners for marriage. Thus language labs in this eddy of ICT

change will need to make brave and

thoughtful decisions regarding why new technologies should be promoted and

whether the theoretical constructs for which these new technologies are

supposedly suitable can be operationalised effectually. One

substantive realisation for language-lab researchers in the current torrent of

technological change should concern the relevance of the ‘humanware’ (Warchauer in-press).

More explicitly, I mean how new technologies might strengthen the age-old and

multifaceted bond between the pupil and human-teacher. Davies et al. (2005, 18) for instance, also hold a comparable

view; they maintain that when considering the installation of a digital lab,

‘the first question that the modern foreign language (MFL) teacher needs to ask

is to what extent the equipment is capable of enhancing tried and tested

pedagogies and methodologies’.

There is also a danger in the current and innovative

drive to brand-stretch key

language-lab services, with the possible effect of enabling a language lab to

take on a more prominent role in its educational institution, that the language

lab may lose its traditional identity as a place to learn foreign languages.

Moreover, it is in this area that innovative research regarding what is

effective and practicable is needed. Finally, research is also required to

assess, in spite of all the new lab gadgets and theoretical constructs,

how prevalent audio-lingualism still is in the learning of foreign languages in

modern language labs.

Word Count 3400

7

References

Alexander, C (in press). A case study

of English language teaching using the Internet in Intercollege’s language

laboratory. The International Journal

of Technology, Knowledge and Society, (3).

Will also be available on http://ijt.cgpublisher.com/

Asher, J. (1969).

The total physical approach to second language learning.

Modern Language Journal, 53, 3-17.

Barnes, D. (1976). From

Communication to Curriculum. London: Penguin.

Beatty, K. (2003). Teaching and Researching

Computer-assisted Language Learning. Essex:

Pearson Education.

Becta.

(2006a). Making a difference with technology for learning: evidence

for school leaders. Coventry: Becta. Retrieved May 10,

2007

from http://publications.becta.org.uk/display.cfm?resID=25961&page=1835

Becta. (2006b). Delivering

the national digital infrastructure: An essential guide. Coventry: Becta. Retrieved May 10,

2007

from http://publications.becta.org.uk/display.cfm?resID=25929&page=1835

Becta. (2007a). How

technology supports 14-19 reform: an essential guide. Coventry: Becta. Retrieved May 10,

2007

from http://learningandskills.becta.org.uk/display.cfm?resID=31532

Becta. (2007b). ICT and e-learning in further

education: management, learning and improvement. Coventry: Becta. Retrieved May 10,

2007

from http://publications.becta.org.uk/display.cfm?resID=28534&page=1835

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching

and Researching Autonomy in Language Learning. London: Longman.

Breen, M. & Candlin, C. (1980). The

essentials of a communicative curriculum in language teaching. Applied Linguistics, 1(2), 89-112.

Brumfit, C. & Johnson, K. (1979). The Communicative Approach to Language Testing.

Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Candlin, C. (1981). Form, function and strategy in communicative

curriculum design. In C. Candlin (Ed.), The Communicative Teaching of

English: Principles and an Exercise Typology (pp. 24-44).

Harlow: Longman.

Chaudron, C. (1988). Second Language Classrooms: Research on

Teaching and Learning. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1964). Aspects

of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

Condie, R. & Munro, B. (2007). Impact of ICT in Schools—a

landscape review. Coventry:

Becta. Retrieved May 10, 2007 from http://publications.becta.org.uk/display.cfm?resID=28221&page=1835

Coughlan, S. (2007). Education,

education, education. BBC News (online). Retrieved May 14,

2007

from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/education/6564933.stm

Curran, C. (1976).

Counseling-Learning in Second Languages. Apple River:

Apple River Press.

Garcia, N. & Wolff, L. (2001). The Lowly Language Lab: Going Digital. Retrieved May 21, 2007

from http://www.techknowlogia.org/TKL_active_pages2/AboutUs/main.asp

Davies, G., Bangs, P.,

Frisby, R., & Walton, E. (2005). Setting up effective digital

language laboratories and multimedia ICT suites for MFL. The National Centre for

Languages as part of the Languages ICT initiative. Retrieved May 25, 2007

from http://www.languages-ict.org.uk/managing/digital_language_labs.pdf

The

Department for Education and Skills (DfES).

(2006). 2020 Vision Report of the Teaching and

Learning in 2020

Review Group.

The

Department for Education and Skills. Retrieved May 10,

2007

from http://publications.teachernet.gov.uk/eOrderingDownload/6856-DfES-Teaching%20and%20Learning.pdf

Ellis, R. (1998).

Discourse control and the acquisition-rich classroom. In W. Renandya & G.

Jacobs (Eds.), Learners and Language Learning, 39: 145-71

Freire, P. (1974). Education for Critical Consciousness.

London Sheed and Ward.

Gattegno, C. (1972).

Teaching Foreign

Languages in School: The Silent

Way. NewYork: Educational Solutions.

Kelly, G. (1963). A Theory of

Personality. New York:

Norton.

Kilpatrick, W.

(1921). The Project Method. New York: Teachers

College Press.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning:

Experience as the

Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Krashen, S. & Terrell, T. (1983). The Natural Approach: Language Acquisition in the Classroom.

Oxford:

Pergamon.

Little, D. (1997). Language

awareness and the autonomous language learner. Language Awareness, 6(2/3), 93-104.

Lozanov, G. (1978). Suggestology and Outlines of Suggestopedy.

New York:

Gordon and Breach.

Nunan, D. (1992).

Collaborative Language Learning and teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Riley, P. (1988). The Ethnography of autonomy. In A.

Brookes & P. Grundy (Eds.), Individualisation

and Autonomy in Language Learning (pp. 12-34).

ELT Documents 131:

Macmillan).

Rogers, C. (1969). Freedom to Learn. Columbus,

Ohio: Charles E. Merrill.

Schoenherr, S. (2005). Recording Technology History.

Retrieved May 20, 2007 from

http://history.sandiego.edu/GEN/recording/notes.html#origins

Toth, J. (2003).

Language

Laboratories and Archives (Chicago University). Retrieved May 20, 2007 from http://languages.uchicago.edu/old/lla.css

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society: the

Development of Higher Psychological

Processes. Boston:

harvard University Press.

Warschauer, M., & Healey, D. (1998). Computers and language

learning: An overview. Language Teaching, 31, 57-71.

Warchauer, M. (in press).

Networking the Nile: Technology and

professional development in Egypt.

In J. Inman & B. Hewett (Eds.), Technology and English studies:

Innovative professional paths. Mahwah, N. J.: Lawrence Eribaum.

Widdowson, H. (1978). Teaching Language as Communication. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Yalden, J. (1983).

The Communicative Syllabus: Evolution, Design and Implementation. Oxford: Pergamon.